Intro and simple setup

Hi, welcome back to Getting Started with Django. Those of you following along in real-time, I'm sorry it's been so long since the last episode. But, even with the time gap, since we're starting a brand new project, it shouldn't be that hard to jump back in.

I've already done vagrant up and vagrant ssh so I'm SSH'd into my virtual machine. Once there, the first thing I want to do is create a virtual environment, so I'll run virtualenv lending-venv and let it install pip. Then I'll source lending-venv/bin/activate and you can see that it adds the virtualenv to my prompt.

Now I need to install a couple of things. First, I'm going to install Django and I'll specify that it needs to be between 1.6.0 and 1.7.0. Generally, the changes within a major release are so minute that we don't really care too much about that third number, but we want to make sure we don't jump all the way up to 1.7.

Our first app was done in 1.4 and there are some significant differences between 1.4 and 1.6, which we'll talk about along the way.

I also want to install psycopg2 since we'll eventually be using a Postgres database. Along with that, we'll also want to do createdb lending to create our lending database. I've already done this so mine will return an error, but yours shouldn't.

Files

Let's go to the /vagrant directory, which holds our cookbooks and projects and everything. And in /vagrant/projects, let's use django-admin.py startproject lending to start our lending project. Back on our host machine, we can open up the lending directory and check what Django gave us.

manage.py hasn't really changed. Our lending directory, which, as you'll remember is sort of a stub app that will act as a central control area for our project, holds our settings.py. Open that and you should notice right away how much simpler it is than the old one.

This is great because it gives us less to customize and worry about. But, don't worry, we still have access to all of the old settings. They're just given sane defaults. Also, notice that the settings are commented as being "not for production". We'll need to adjust several things before we make the project live on a server.

It's nice that Django now imports os and sets up this BASE_DIR variable. These two basically let us ignore that root lambda that we created in our old project.

But, like our old settings, I still like to rename the default INSTALLED_APPS to DJANGO_APPS and then add two empty tuples named THIRD_PARTY_APPS and LOCAL_APPS. Of course, to make Django happy, you'll need to recombine these into INSTALLED_APPS by concatenating them all together.

Another Django 1.6 change is that django.contrib.admin is turned on by default in the settings and in urls.py. Also, Django gives us a usable SQLite database. We'll leave it alone for the moment but we'll replace it with Postgres before the end of the episode.

STATIC_ROOT and MEDIA_ROOT are both missing from the settings. Since we're not worried about site-wide static files or user-uploaded media yet, we'll leave them out. STATIC_URL, though, is set so that our admin can find its files.

So we'll save that and hop back over to our terminal and go into the lending directory. But we aren't going to sync our database just yet.

Custom Users

For our lending project, we want to have custom user models. Usernames are often very different from site-to-site, depending on if other people got there before you or whatever. So, to make things easier, let's have a custom user model that just uses email addresses.

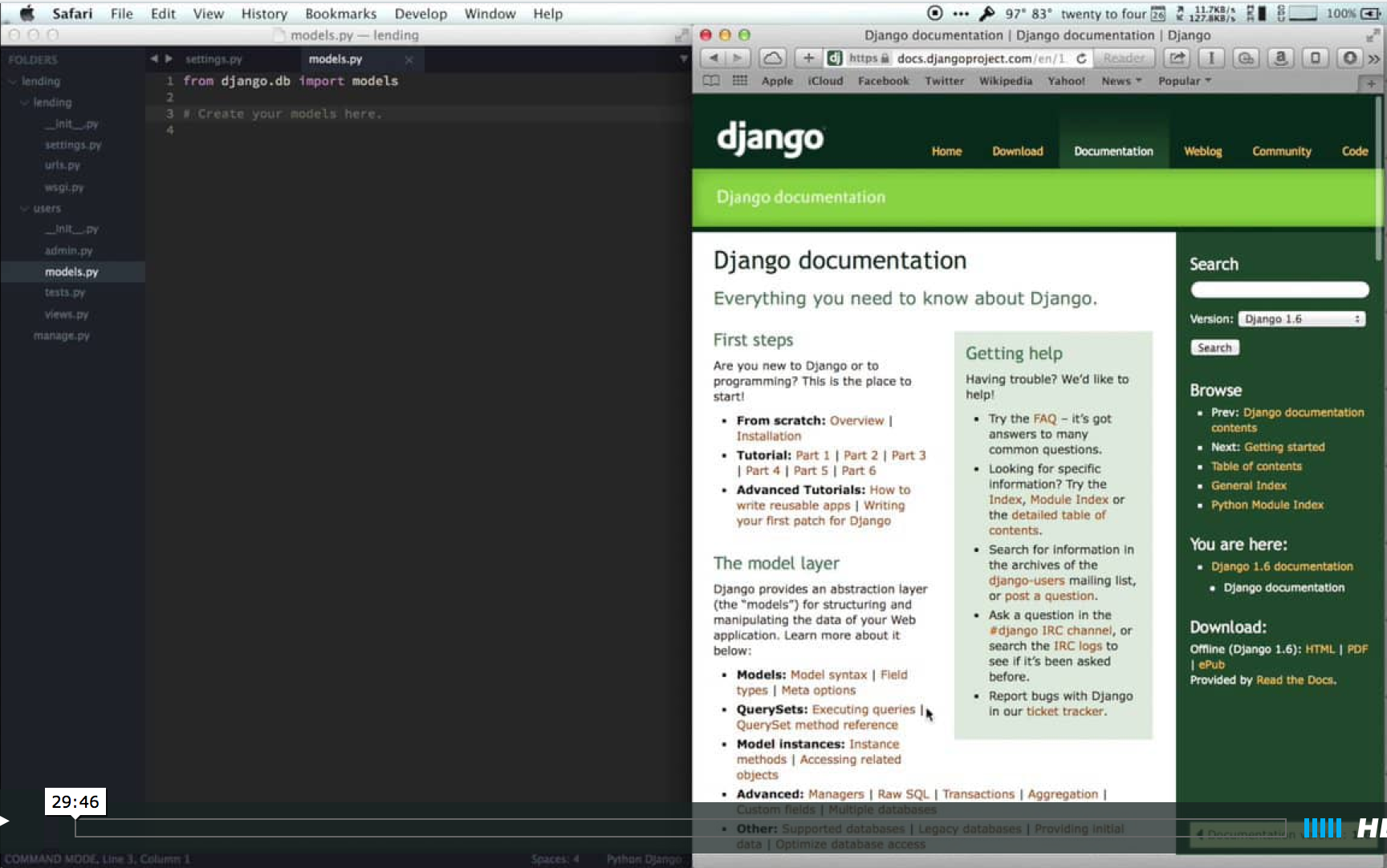

So let's make an app that'll hold onto the users. Let's run python manage.py startapp users. Now, the users name isn't special; we could call it accounts or people or whatever we wanted. If we look in the users directory, it contains nothing new. Before we move on, though, let's go to the Django docs and down at the bottom there's a link for Authentication and at the bottom of that is Customizing Users and authentication which is exactly what we want to do.

On the right hand side is a link for Substituting a custom User model and since it's always a good idea to have the docs open, let's go to that area. There are a lot of good docs in here, so it's well worth the read, but what we're most interested in is this AbstractBaseUser that Django gives us.

In our users/models.py, we need to import the AbstractBaseUser from django.contrib.auth.models. Then we'll start with our custom user. We'll call the model User and it will extend AbstractBaseUser of course. AbstractBaseUser doesn't give us a lot by default and has some requirements.

It requires an ID, but that comes standard on Django models. It has to have some sort of identifier field that's unique. That'll be our email address. And we have to have two methods for addressing the user, one for "short" and one for "long".

Let's give our users an email address, which we'll call email and make it an EmailField. We'll set the max_length to 100. I think it unlikely someone would have email address longer than 100 but if you're worried about that case, feel free to make the field longer. We'll also mark it as unique. In the model, we have to provide an attribute named USERNAME_FIELD, so let's go ahead and add that and set it to 'email' which is the name of our unique, user-identifying field.

We can also provide other fields on the model, of course. We'll add a field for the person's name, a CharField that we'll give a max_length of 255 and we'll set blank to True in case they don't want to specify a name.

We don't have to worry about providing a field for the password; Django will give us that in AbstractBaseUser, along with methods for getting and setting the password securely.

We'll also add a couple of BooleanFields that hold whether or not a user is active and if a user is an admin. We'll set the is_active on to be False by default, so we can have users click a link to activate their account. We'll also set is_admin to be False because we don't want just everyone to be an admin.

There's an optional attribute we can set on our User model named REQUIRED_FIELDS and these are the fields that are required to have values set on every user. Since we don't have anything that doesn't have a defalt and is required other than our email address, we can leave this attribute off.

We also need a few methods on the model. First, we'll do get_full_name which will return self.name if it exists, otherwise self.email. Then, we'll define get_short_name and have it always return self.email. We could write our get_full_name a couple of different ways, such as:

if self.name: return self.name else: return self.email

Which is the same code but more verbose. It might be more readable, though, so use whichever version you're more comfortable with.

We also want, as always on Django models in Python 2, to define __unicode__. We'd want to define __str__. We'll have __unicode__ return self.email. We'll worry about permissions more in a bit, but we do need to define an is_staff property to control whether or not a user can log into the admin. We'll make it return the value of our instance's is_admin so admins are guaranteed entrace to the admin area. This is obviously a bit naive, though, and if we wanted admins that weren't privvy to the Django admin area, we'd have to control this differently, of course.

Custom User Manager

Before we can start to actually use our users, though, we need to create a manager for them that defines, if nothing else, how to create standard and super users.

We'll create a new class called UserManager and it'll extend BaseUserManager which we need to import from django.contrib.auth.models as well. You can do them as one import or two, doesn't really matter. I'll likely combine these in a later video to save some room.

In our manager, we need to create two methods. The first is create_user which'll take self, our user's email address, and an optional name. If they don't give us an email address, we want to raise a ValueError or, if everything's good, we want to create the user, set the email to what they passed in passed through Django's normalize_email function which just normalizes emails by lowercasing the domain portion. We'll also set the name to whatever name they passed in. Then we'll set the password on our in-memory instance to the password they sent in. This set_password function handles hashing and salting our passwords. We also need to be sure and add a password argument to the method call. Finally we'll save the user and return it.

Our second method is create_superuser which takes all the same arguments. We call create_user and pass in the submitted email, name, and password. We'll set is_admin to True on the instance and then we'll save the user and send it back.

Lastly, we need to register the manager with our model. So we assign objects on the User model to be an instance of the UserManager class. This passes methods to the UserManager whenever we call User.objects on anything (like User.objects.filter()). If the method doesn't exist on UserManager, it moves up the inheritance chain.

Finally, go back to our settings. In LOCAL_APPS, we need to add 'users', to the tuple so the app will be registered with Django. And, somewhere else in the file, we need to set AUTH_USER_MODEL and set it to 'users.User'.

Create a new user (problems!)

Let's see how our model changes things.

Back in our terminal, we can run python manage.py syncdb. It'll do the normal work of creating tables and when it asks, go ahead and create a superuser.

If you remember the old project, it would ask for a username first, but ours asks for email! This is because our user model doesn't have a username field and we've told it that the "username" field is actually email. Then it does the normal double password prompt. And instead of working ours complains about not having a name.

Let's fix that back in users/models.py. We'll change the create_superuser method around so that we explicitly set name to be optional.

If we try and run syncdb again, nothing happens because the database has already been synced. So let's do createsuperuser instead. Again, we enter an email address and a password twice.

And again it fails. This time it says the name is NULL and can't be. OK, so let's give a default value to our User model, so if it doesn't get anything for name, it'll use an empty string. Try createsuperuser again and....

Another failure. OK, maybe something is wrong with the database. Since we're using SQLite, we can just delete the db.sqlite3 file and our database is "reset". Then we'll run syncdb again which recreates all the tables. Let's create another superuser.

Actually, in experimenting after I recorded the video, I found out what I'm doing wrong. We'll fix it the correct way at the end of the video, but I thought it beneficial to show you my debugging and solving process in this one, and to show that even seasoned developers make stupid mistakes from time-to-time.

It's still failing. What have I done wrong? Well, it's complaining about name being NULL so let's allow null in our model field. We really shouldn't do this since it's a CharField but maybe it'll make it pass.

Since we've changed a field from NOT NULL to NULL, we need to recreate the database, so delete the db.sqlite3 file again and re-run syncdb. And now, when we create a superuser, it goes through just fine.

If we apt-get install sqlite3, we can run sqlite3 db.sqlite3. In there, we can use .tables to show us all of the tables and we see that auth_group exists but Django's default auth_user isn't there. We can also run select * from users_user; and we'll see our superuser that we created. ctrl-d gets us out of SQLite.

So we have a custom user and a custom manager that are "special" because they let us create superusers and stuff, but they're still just Django models and managers. If we go into python manage.py shell, we can import User from users.models and create a new one just like we'd create any other instance. We could also call create_user and it would run the method on our manager. Inspecting our object shows us our predicted values for things like is_admin and is_staff.

We can also select our superuser by querying for the email address. Looking at is_admin and is_staff on it give, again, predicted values. We can set and save a name and then call our two name methods and get out what we're expecting to.

The Admin

My VirtualBox has changed a bit. Normally I'd go to 127.0.0.1:8888 but apparently it's now 127.0.0.1:2201. Not a big deal, but something to point out in case yours is different too.

So going to the / gives us the "It Worked!" page and going to /admin/ shows us the usual log in page. I should be able to put in my email address and password and log in. Also, notice that the form now asks for "Email" instead of "Username".

If I put in the standard user's email and password, I'm not able to log in. Good, that's the behavior we expected. What happens if I put in my superuser's info?

Hmm, I'm not allowed in. Even when I double-check the password, I'm still not logging in. We probably need to set up the permissions on our user.

So back in users/models.py, in the User model, let's add a couple of new methods: has_perm and has_module_perm. has_perm takes self, perm, and obj, which can be None, but we just return True. We do the same work in has_module_perm but it only takes self and app_label. Neither of these gives us any real permissions, but they should help on getting us into the admin.

So, back to /admin/ and we still can't log in. What else could be going on with our user model? I'll split my tmux window and get into the Django shell again. Bring in the User model and grab my superuser's user instance. It's correctly set as staff and as an admin and I'm pretty sure the password is right. Let me double-check that I typed the email correctly. I did, OK, something else.

Again, it was a silly mistake. Set the user's is_active flag to True, save, and try again. Now I'm in!

Inside the admin, we only have access to the "Groups" admin area because we haven't defined the admin settings for our users app. Before we do that, though, we should pay more attention to permissions.

Permissions

Django provides a PermissionsMixin in django.contrib.auth.models and we should import it. We then add that to our User model and that'll let us set a user as belonging to groups. Since we now have the ability to check if a user has permissions, we can remove our useless permissions-checking methods from the User model.

Back in the shell, if we run python manage.py sqlall users, we'll see all of the SQL commands that Django would run for our users app. We can see in it that there are now tables for joining groups and permissions to users. We need to delete and recreate our database again so that all of this is cleanly inserted. We'll go ahead and create the superuser again.

Again, though, our user is inactive. This is getting annoying so let's fix it once and for all.

Our superusers should be active by default, so in create_superuser, let's add another line to set user.is_active to True. That'll work for the future but we'll just fix the existing one in the shell, although you should feel free to delete your superuser and use the createsuperuser command again if you want. Now we can log in. But our user has no permissions to edit anything.

If we check our user's is_superuser attribute, we now get that it's False. This attribute comes from the PermissionsMixin, by the way. So we want to set that as True in the shell, but we also want to modify create_superuser to set is_superuser to True by default, too.

If we refresh the admin, we now have access to everything. Since we have the PermissionsMixin and its is_superuser attribute, we probably don't need our old is_admin attribute but we'll leave it alone for now.

Forms

We do want to be able to edit and create users in the admin. Helpfully, Django gives us some solid examples of the admin class and forms we need to make this possible, so let's create them.

First, we want to create users/forms.py. If possible, we want to make one or two forms that we can re-use in other parts of our app instead of making them just for the admin. We might not end up using them but it's nicer to have them waiting for us than to have to refactor them out later.

We'll import forms from django and we'll bring in the ReadOnlyPasswordHashField from django.contrib.auth.forms. This field is really useful because it shows us the hash of the password but not the actual password itself, since we don't want to expose people's passwords to just anyone.

From our .models, we need to import User. At the top of the file, though, we should add another import. from __future__ import absolute_import and that'll make it so that our relative imports behave appropriately.

Now we'll start a new form named UserCreationForm. It's just a ModelForm but we need to create a couple of special fields.

password1 will be a CharField with a label of 'Password' and a widget that's set to forms.PasswordInput. This will make the widget mask the password as it's entered. password2 is pretty much a copy of password1 but with 'Repeat your password' as the widget.

Our form's class Meta will have a couple of special settings. We'll say that the model is User since that's the model we want to use, and we want to restrict the fields to just 'email' and 'name'. We don't want to show is_active or is_superuser or anything like that. We could show is_active if we wanted but it's probably better to show that only on the editing form.

We need to set up a clean_password2 method that'll let us compare the passwords. First we set password1 equal to the cleaned_data value and the same for password2. Since we're using .get() on a dictionary, if either doesn't exist, we'll get back None.

If we have values for both, but they don't match, we'll raise a ValidationError saying that the passwords don't match. Otherwise, things are OK, and we'll just return back the value of password2.

We'll also override save. We'll super() it to get the default user but we'll pass in commit=False so it doesn't write to the database right away. Then, on our user instance, we'll call set_password with the data that's in cleaned_data['password1']. We already know that there's a value there and that both passwords match, so this is a safe operation. Then, unless we've been told explicitly to skip the commit, we'll save the user and, either way, return it.

So now let's look at the UserChangeForm. This is also a ModelForm and we're only going to define the password field on this one. We don't want to show the actual password, we want to use that ReadOnlyPasswordHashField that we imported earlier.

In the Meta, we set the model to User again and this time we set fields = ('email', 'password', 'name', 'is_active', 'is_superuser').

Since we're using is_superuser instead of is_admin, let's remove is_admin from our model and change is_staff to return us the value of is_supeuser instead. We'll want to recreate the database after this step, too, since the is_admin field still exists there.

Back in our form, we want to override the clean_password method. Since we aren't allowing anyone to set the password through this form, we want to just return whatever value was in self.initial for 'password'.

User Admin

Now open up users/admin.py. I'm not sure why I imported Group but you don't need it. We do need to import UserAdmin from django.contrib.auth.admin, though, and we also want to import our User model and both of our forms. We'll also do the from __future__ import absolute_import import at the top.

Our class is going to be CustomUserAdmin and it'll extend the UserAdmin from Django. The form we'll set to UserChangeForm so it'll be used for editing. We'll set add_form to UserCreationForm so it'll be used for adding new users. In the list_display, let's show the email, the name, and whether or not the user is a superuser. We'll set up a filter for is_superuser.

We'll create this add_fieldsets attribute. This isn't standard on ModelAdmin instances but the UserAdmin class uses this in a special way to control the fieldsets that are show on the add_form. We'll give it a single fieldset with no label, set the classes to wide, and set the fields to be 'email', 'name', 'password1', 'password2'.

We'll also add a couple of fields for searching, email and name. And we'll order the records by email. And, lastly, we'll specify that groups should use a horizontal filter.

The final step is registering our model with the admin and its custom ModelAdmin. And since I don't actually need the Group model, I'll remove that from my imports. If we go back and refresh the /admin/, we'll see our Users app listed.

Let's go look at the users. There's just one with no name but you can see the email and the superuser status. If I click on it to edit it, though, I get a FieldError. Where this problem really exists is in our CustomUserAdmin and its lack of a fieldsets attribute.

So let's define one. We only need one fieldset, it doesn't need a label. Its fields will be a tuple of 'email', 'name', 'password', 'is_superuser', 'is_active'. And if we refresh we can see all of our expected fields, including the password salt.

Let's go back and add in another fieldset named 'Groups' and it'll hold the groups field. Refreshing shows us the groups for our user.

Database

Now let's get rid of the SQLite database and use our Postgres one that we created at the beginning. In the settings file, there's a URL to Django docs about setting the database. We need to change our ENGINE from sqlite3 to postegresql_psycopg2 and then change the NAME the 'lending' and then set the USER, PASSWORD, HOST, and PORT values, too.

Now, if we go back to the terminal and run python manage.py syncdb, it creates our tables in our Postgres database and asks us to create a superuser again. Everything should be working and we shouldn't have to modify our user at all. Refreshing the admin will make us log in since the sessions table is now empty but we should be able to and nothing will have changed inside the admin.

Conclusion

That has us up to a pretty solid point for a first episode. We have a new Django 1.6 app with custom users and custom functionality for them in the admin. In our next episode, we'll go through authentication and registration for our users.

Thanks for watching!

Addendum

Hey everyone. Sorry, just wanted to address a quick issue I found while I was editing the video.

When we tried to create a superuser, we got errors about the field being NULL when it shouldn't have been, so we changed the field to null=True. Well, that's a bad decision in Django because because now our field has three possible states: it has a value, it has a false-y value like an empty string, or it's NULL, which is also false-y but not in the same way. We don't want that. Apparently I went a bit brain dead while I was recording the first time, so let's fix that.

First of all, we don't want this field to be nullable, so let's change null to blank. The model is now fine and dandy and just how we want it to be.

Now, though, let's go edit the two methods in our manager. In both of these, we set name to None if one isn't passed in. This actually sets the missing name to None in Python and None is the only thing that's None, so it wasn't falling through and becoming the empty string we wanted.

We could do name=name if name else '' but that's annoying and puts an if condition inside of our method call and that's fairly ugly. Instead, let's set name to explicitly be an empty string in the method calls. Since strings are immutable, this is an OK operation to do, unlike doing the same with an empty dictionary or list. We'll make that same change on both methods.

To test this, we need to drop and recreate our database. Then we can run syncdb and create a superuser and...it works!

Again, thanks for watching and sorry for writing bad code earlier!